Peggy Vermeesch interviews Jungian analyst Mark Saban, author of Two Souls Alas: Jung’s Two Personalities and the Making of Analytical Psychology. We explore the basic premise of the book, its clinical implications, and Saban’s motivations for this work, which he presented in the 2019 Zurich Lecture Series.

French version of this interview

This interview centers around Mark Saban’s book Two Souls Alas: Jung’s Two Personalities and the Making of Analytical Psychology.

On this Page

- Introduction

- Jung’s two personalities

- A psychology that prioritizes the No. 2 personality

- Individuation of the Jungian world

- « We are Jungians »

- Source of the strong affect in the book

- Jung’s countertransference

- Contradiction between theory and practice

- Writing as part of individuation

- The interactive field

- The affective aspect of the archetype

- Writing as snapshots of thinking at a moment in life

Introduction

Peggy Vermeesch: In the conclusion of your book, you rephrase its overarching idea in the following way: that in order for analytical psychology to truly follow Jung’s basic premise, his ideas must individuate, and thus: « be brought into tension with whatever they lack. Unless Jung’s ideas meet such a challenge … they will calcify and die, or worse, become the dogma of a cult. »

Mark Saban: To be honest, I think everything individuates. For Jungian psychology itself to individuate, the ideas of the participants, including mine and yours, would need to individuate as well.

If we treat Jung’s writings as unchangeable truth, no individuation will occur. Quoting Nietzsche, Jung writes to Freud that one repays a teacher badly if one remains forever a pupil. To respect your teacher, you must leave them behind, develop new ideas, build on what you’ve learnt, and even fight against it.

Jung’s two personalities

A guiding thread throughout your book is your discussion of Jung’s experience of having two personalities, which he had such trouble reconciling, that it reverberated through the subsequent development of his psychology: a struggle that continues to affect how Jung’s theories are practiced and taught today. Could you shed some light on this split which originated early in life?

In the first chapters of Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung describes his childhood and his two personalities. Personality No. 1 was his ordinary self who went to school and had friends. Personality No. 2 connected him to infinity and spirituality through dreams, visions, and games. Oddly, Jung felt more comfortable in this second world. Given half a chance, he preferred living in personality No. 2, while No. 1 was an annoying necessity just to be in the world.

He is very tempted to communicate this No. 2 world to others. But he’s terrified they’ll laugh, reject it, and see him as mad. He reads about Nietzsche and infers a similar relationship to this other world. Nietzsche made the mistake of divulging it and went mad. Jung is terrified of becoming Nietzsche, so he keeps this world a secret but never loses contact with it.

When he talks about those early transformative experiences, he imagines two channels merging into one great river. He means that when personality No. 1 and No. 2 come together, they have the power to really move one on and enable transformation.

You cite Jung: « the two currents of my interest could flow together and in a united stream dig their own bed » (Jung, MDR, p. 109).

Exciting new creative things can happen when that occurs, however difficult the tension between the two. This is the origin of Jung’s idea of the transcendent function, crucial to individuation, which I see as central to Jung’s psychology. In my book, I trace Jung’s core ideas back to his experience with the two personalities.

A psychology that prioritizes the No. 2 personality

I suggest that throughout his life Jung tended to be pulled in the direction of his personality No. 2, and that this created a bias towards the world of dreams, symbols, myth, archetypes, alchemy, and the collective unconscious. Jung had relatively little interest in personality No. 1 things: ordinary relationality, living in the world, connecting socially and politically.

With one exception: he does put a lot of energy in the advancement of his ideas.

Yes, Jung is not a sort of mystic isolated on a mountain. He spends his life publishing, traveling, and connecting with people. But if you read his memoir, that’s not the bit of his life he chooses to emphasize. There is that tension in Jung all the time: the tension between personality No. 1 and 2, between outer life and inner life.

In a way, Jung managed to straddle this tension quite well. Perhaps Jungian psychology after Jung has done this less well. At one extreme there’s a tendency to lean heavily towards the internal, intrapsychic, symbolic, and archetypal realms. Conversely, there’s also the developmental branch in the Jungian world, which focuses much more on transference/countertransference and everyday life issues.

But the trouble is that in order to maintain that interest, those Jungians have felt obliged to bring in a lot of ideas from psychoanalysis, and particularly from the Kleinian world. My argument in the book is that is that this isn’t necessary. If we want to avoid one-sidedness, we just have to find the outer-facing personality No. 1 dimension of analytical psychology and allow it to come into tension with the dominant personality No. 2 side. That is exactly what Jung’s notion of the transcendent function is all about – bringing into play what is missing.

It’s unfortunate that those most drawn to Jungian psychology are often those who might need it the least, as they are already fascinated by fairy tales, myths, and their own dreams and inner life. Classical Jungian analysis tends to emphasize these aspects even more. In a way, those people might benefit more from psychoanalysis, while those drawn to psychoanalysis ought to come to Jungian analysis. And then something really interesting might happen.

But, of course, I’m just as guilty of that myself because I was just as fascinated by the inner world. That’s why I chose to go into Jungian analysis. And that’s why I’ve spent quite a lot of my life working within the Jungian world.

Individuation of the Jungian world

But the individuation of the Jungian world requires this other side that’s been neglected. And it’s not a question of swinging across from the archetypal to something completely different. It’s a question of bringing the archetypal into play with the outer world, with the everyday world, with the social, the political, and so on.

When I read your book, I thought I sensed some anger directed at Jung, or perhaps later Jungians who « imitated Jung’s one-sidedness in a trivial and superficial way, thereby locking themselves into a very narrow, inward-looking perspective, dogmatizing Jung’s psychology, and obsessively revisiting those themes that Jung favored. »

Yes, you’re right, I’m not entirely happy with that.

It’s frustrating because I see it as a waste to do this with such exciting and groundbreaking ideas. I think the Jungian world tends to stay within its comfort zone, which contradicts the essence of individuation.

Individuation is about breaking out into the new, taking risks, daring, and being open. Too often, I think Jungians may feel they’ve achieved this in their own analysis or training, but then settle into a sense of knowing everything once they reach that safe zone.

Like the fully analyzed analyst?

Exactly. It used to be more common that people would say: she or he is individuated, which is such nonsense. It’s obvious from what Jung writes that there is no end to individuation. It goes on, and on, and on.

Individuation is not enlightenment.

Yes, and that’s the trouble. Jungian psychology has always been dogged with this slightly culty feel to it. Once you’re enlightened, you become a master and impart your wisdom to your pupils. That was the dynamic that played out in Zurich for many years, I think, although there was always a mercurial side of Jung that disrupted it as well.

And that’s fine. Jung was who he was, like all of us. And he makes no bones about it: he emphasizes that his psychology comes out of his own personal equation. « I am what I am, and here’s my psychology. » I find that to be quite a challenge for us as Jungians.

« We are Jungians »

It’s problematic, in a way, that we call ourselves Jungians.

If you’re a psychoanalyst, you typically don’t label yourself as a Freudian unless you’re distinguishing yourself from another branch. You’re simply a psychoanalyst. Although Jungians also use the term analytical psychologist, we are usually identified as Jungians, which aligns us closely with the figure of Jung.

He is obviously a huge, colossal figure, and sometimes it feels like the Collected Works loom over us, threatening to crush our own puny efforts. But we’ve got to try at least to push against that, and move things along, because it’s not all about Jung. It’s about the ideas. And even though the ideas come out of Jung’s personal experiences and that’s what gives them value, we also have to take into account the fact that those experiences are Jung’s experiences alone, and if we want to keep them alive we need to make the ideas ours.

Source of the strong affect in the book

I find it interesting what you picked up from the book, especially the frustration, some of which was directed at Jung. Shortly after the book was published, I did an online seminar with a group of Jungian analysts in New York. A very eminent Jungian analyst, whose work I admire, asked me with her first question: « Why do you hate Jung so much? » I was really shocked by that and thought: is that really what I’ve written, a book that hates Jung?

She might not have read to the end!

Probably not. I’ve spent most of my life working with Jung’s psychology: I write about it, I read about it, I teach it, I work as a Jungian analyst. So, if I hate Jung, then there is a problem there. I don’t think I hate Jung, but that doesn’t stop me from being able to be critical. We do Jung no favors if we fail to bring to bear a critical eye.

Jung’s countertransference

While reading, I also wondered if you thought that Jung was perhaps not courageous enough to be honest about his countertransference feelings when writing about his case studies.

Jung was extraordinarily courageous in developing his own psychology. He gave up a lot, including his valuable relationship with Freud and his place within psychoanalysis, because maintaining those things became impossible for him. This courage wasn’t an act of the ego, but something driven by the unconscious. He knew a lot of people would find his psychology difficult, because he was pushing against the current of rationalism and the prioritization of the intellect. Reacting against this wave required significant courage, so I’m not criticizing him for any of that.

In the book, I focus on his case with Christiana Morgan. It’s clear from both his account and hers that this was not a successful case. I suggest that this is due to Jung not addressing his own countertransference or taking her transference seriously. Instead, he imposes his own dogma about archetypes onto the material she’s producing, insisting in a way that she replicate his work with The Red Book.

He’s being very directive, even regarding her personal life. Doesn’t he encourage her to create a similar arrangement to the one he had with Emma and Toni?

Yes, he does. And he says that her main task is to contribute to the individuation of her man, just as Toni Wolff had helped him. « You’ve got to give yourself up and become a kind of muse or an anima figure. » I think most people nowadays would see that that was perhaps problematic on all sorts of levels.

Contradiction between theory and practice

The difficult question is why addressing countertransference was so hard for Jung. There’s a strange disjunct between his approach in certain cases and his writings on psychotherapy. There is a whole volume of his Collective Works on psychotherapy, including The Psychology of the Transference, published in 1946, where he’s totally ahead of the game regarding countertransference.

He emphasizes the mutuality of therapy, the fact that nothing transformative happens unless the therapist is completely present in the therapy, and he discusses the concept of a transformative field: a sort of third, which operates within analysis. All that is very forward thinking and revolutionary almost. And yet we don’t see any of that in his case studies.

To be fair, the case with Christiana Morgan was in the 1920s and The Psychology of the Transference was published in 1946. But there are earlier texts by Jung on psychotherapy which point in the same direction. So there does seem to be an interesting disjunct there.

Jung is allowed to get things wrong, reflect, and develop new ideas. I’m sure that a lot of his revolutionary ideas, especially in The Psychology of the Transference, likely came from his own personal experiences in analysis. He often had difficulties, especially with his women patients. There’s much to learn from Jung’s mistakes, and that’s what I am trying to do.

In 1935, in the Tavistock lectures, Jung talks about working with dreams, and he differentiates personal dreams from archetypal dreams. Personal dreams involve engaging with the client’s associations, while archetypal dreams involve interpreting symbols based on myths and legends. This split approach feels to me like he’s not doing justice to his own ideas.

The whole idea of the transcendent function and individuation is about avoiding one-sidedness by bringing opposites together. You need to find what’s missing and bring it into play. And out of the tension between the two comes the new perspective, the new idea.

That is the process of individuation throughout life. And there’s no end to it.

The personal and the archetypal are good examples of these opposites. It’s what happens when the two come together that’s interesting. That’s what moves things on.

And it seems to me that that is the logic of what he says in The Psychology of the Transference about the way in which psychotherapy works as well. I’m not saying anything very new in the book. I’m merely bringing to bear Jung’s own ideas onto areas that he himself doesn’t seem to have seen in that way.

Writing as part of individuation

I wondered how the writing of this book was part of your own individuation process in terms of holding the tension of what I imagine must have been two very opposite viewpoints and feelings. On the one hand, your interest and love for analytical psychology, resulting in your training, research, and teaching. And on the other hand, I imagine you must have had serious questions and doubts. Where did these come from?

From an outer world perspective I wanted to write something about the opposites because I felt that there was a kind of gap in the literature. No one seemed to have devoted an entire book to the idea of the opposites, even though this seemed to come up in almost everything Jung wrote. But, the more I looked at it, the more glaring it seemed to me that there was a one-sidedness, not just in Jung, but in the Jungian world.

Then, alongside that, and probably more importantly, it was my clinical work that guided my interests. As an analyst I started very much on the archetypal end of the spectrum, which is as far away as you can get from the developmental end.

In my training, I got almost nothing on transference/countertransference, which was considered a narrowly, reductively clinical dimension. Instead, I got a lot of knowledge about archetypes, fairy tales, myths, and so on. That’s what I was attracted to. I didn’t want to have anything to do with what I thought of as psychoanalytic nonsense.

And I kind of got away with that for quite a while, but then I had various clinical experiences, which made it very clear to me that this was an area I really needed to work on. It opened in me a hunger for finding a way to think about the dynamics that go on in the actual room with the actual patient.

I didn’t swing across and become a developmental Jungian. Instead, I had a desire to find what Jung had to say about it, and more importantly, Jungian psychology, if one really got down to bringing to play this notion of the opposites and the transcendent function.

So, when I criticize Jung for the way he worked with Christiana Morgan, what I’m really doing is writing about my own incapacity to deal with that sort of situation as an analyst. And I think a lot of the frustration that the book contains is actually self-directed.

It’s directed at my own feelings of being incapable of doing justice to that and wanting to find a way. But within the Jungian approach rather than bringing in something from outside.

The interactive field

What kind of research have you been doing since you finished writing your book?

I’m still really fascinated by the whole transference/countertransference dimension of things, and particularly the notion of an interactive field, as a third thing above and beyond the individuals involved.

In Chapter Four you explore Jung’s relationships with a series of important women and give special attention to the way in which Jung « tended to internalize aspects of his outer relationships and to appropriate them for the purposes of his inner development ».

When you write about the erotic charge of his relationships with these women (Helene Preiswerk, Sabina Spielrein, Maria Holtzer, and Toni Wolff), you put into question Jung’s (and later writers’) interpretation that they developed an erotic transference onto Jung, positing that maybe it was Jung who started with the erotic projections. Then you write that it’s very difficult to know who was at the origin of these feelings because these things happen in the field.

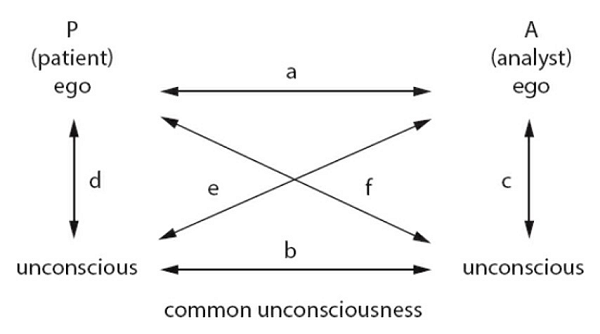

In Jung’s Psychology of the Transference there’s a very useful diagram that shows all the different possible kind of relational vectors that show up within a one-to-one clinical relationship.

Jung’s transference/countertransference diagram, adapted by Mario Jacoby in Analytic Encounter: Transference and Human Relationship.

There are many different possible things all going on at the same time. Is this me? Is this you? Or is there something else going on, which is somehow neither, or rather both? I think sorting that stuff out is so fascinating, so interesting, and so difficult.

Jung brings into play the idea of an unconscious connection from the unconscious of the patient to the unconscious of the analyst, and vice versa. And that is the key bit for the idea of the field: that there is something unconscious in the room, which the diagram cannot do justice to, because the arrows still keep the two separate.

What’s really going on is something much more interesting in terms of a kind of interpenetration, a kind of place in which… It becomes very difficult to find the right language to describe this. But I think the idea of the field helps.

Jungian analyst Nathan Schwartz-Salant has written quite a lot about the field in this context.

I admire him greatly, because he’s incredibly brave. When you’re working with a client, there’s a huge temptation to insist upon « this is yours », « this is mine », and to read everything back into the patient, which is what the original idea of transference is all about.

Which is incredibly frustrating for the patient, who feels like the other person doesn’t want to take responsibility for their part, and that the patient is responsible for everything that happens in this relationship.

The original kind of Freudian blank screen notion was exactly that: you encourage the projections, but you sit behind the screen, as it were, and you observe and interpret them as an objective scientist without any reactions of your own. And the patients are supposed to eventually take their projections back and realize that, of course, it was all about them and their relationship to their parents in childhood, or whatever it was.

Now, obviously, that does happen. But there’s a lot more going on than that, and this is the same conclusion that the relational school of psychoanalysis has come to as Jung did in 1946. The analyst is just as much in the relationship. Jung says that unless both the analyst and the patient are transformed, then nothing is happening at all.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that the analyst spends their whole time telling the patient all about their own stuff. That’s not a good place to go, either. But I think there is a difference in the way in which you’re in the relationship with a patient, if you take seriously the fact that you are actually in this with them. From an alchemical point of view, you’re both in the vessel together, and the heat is under it. And stuff is going to happen there.

It makes it much more challenging and scarier, much harder to know what’s going on, but also potentially much more transformative for everybody concerned.

How would you apply this in a session?

Here’s how Schwartz-Salant describes himself in sessions. When he notices a lot of affect, like anger, in the patient, he addresses it by saying there’s anger in the room and suggests it’s in the field rather than in the patient.

The patient asks: « Whose anger is this? » He responds: « There’s no way to know. Let’s just sit in the anger. » He allows the anger to be present without attributing it, for example, to the patient’s relationship with their father. He says: « Let’s just see what happens when we’re both here, because I don’t know what’s going on either. »

That’s a very courageous way to approach analysis, but it’s very fruitful. It’s also dangerous. So, this is not a safe or easy place to be as an analyst, because you are out of your comfort zone in all sorts of ways.

And you’re very vulnerable.

Yes, those wounded places in the analyst are being engaged. And you’re not trying to close that down: you’re allowing that to be there. Again, you’re not disclosing, you don’t have to be telling the patient all about your personal problems, for it to be open and engaged in the room. It’s really very exciting work! And this is exactly what Jung is pointing out in his piece on the transference.

The affective aspect of the archetype

What we’re talking about is something that’s bigger than the individual, and more powerful in a way. I think it relates closely to what I think the archetypal actually is. Jung says somewhere that the archetype means nothing unless there’s an emotional aspect to it: the emotional side of the archetype is absolutely crucial.

You can talk about myths and legends and fairy tales all you like, unless you’re experiencing it on the affective level, you’re not really in touch with the archetype. But the affect is not just personal. It is also collective.

And I think that’s why it then becomes the field, or the third: because the archetype is bigger than the individual. It’s collective, but nonetheless directly experienced and engaged with by ordinary individuals. It brings together the personal and the archetypal in the same place and that’s the interesting place to be. And we’ve come full circle.

Back to your point regarding the need for the personal and the archetypal to meet: the outer and inner world, the No. 1 and No. 2 personalities.

Writing as snapshots of thinking at a moment in life

It’s interesting to go back to the way we started because I suspect that the book came out of a particular moment and there are all sorts of ways in which my thinking has moved on. I’m not saying it’s better or worse, but it’s in a different place now because that place just marked that particular moment.

I had a similar thought when you were talking about Jung and how we try to understand him based on his writing from different times in his life. In most likelihood, the things he wrote were only a snapshot of how he felt and thought at that particular moment. And once it was written and worked through, he also moved on.

Yes, exactly. And that’s the problem with the Collective Works, which are mainly organized according to topic. In it you find a mixture of early Jung, middle Jung, and late Jung, and it’s all put together as if it were one set of ideas. But it’s not, because Jung was doing exactly what you just described.

For example, the book that instigated the rift with Freud, translated as Symbols of Transformation in CW5, was revised by Jung in the 1950s. He constantly revised and added to his works, making it hard to trace how his ideas developed. Late Jung is very different from early Jung, but this evolution is often disguised, and his ideas are presented as a monumental edifice.

Our job, as well, is to point that out, work away at that, and sort of take it to pieces.

Thank you so much for speaking with me. For those who would like more information, see the presentation of Mark Saban’s book Two Souls Alas: Jung’s Two Personalities and the Making of Analytical Psychology.

Interview conducted by Peggy Vermeesch – July 2024

Mark Saban, PhD

Mark Saban trained with the Independent Group of Analytical Psychologists, with whom he is a senior analyst, working in London and Oxford. He is also the director of the MA in Jungian and Post-Jungian Studies in the Department of Psychosocial and Psychoanalytic Studies, University of Essex.

Publications

Mark Saban co-edited (with Emilija Kiehl and Andrew Samuels) Analysis and Activism – Social and Political Contributions of Jungian Psychology (Routledge 2016) and wrote Two Souls Alas: Jung’s Two Personalities and the Making of Analytical Psychology (Chiron 2019) which won the International Association of Jungian Studies’ Best Book of 2019.

Learn more

Interview Peggy Vermeesch with Mark Saban centered around his book Two Souls Alas.