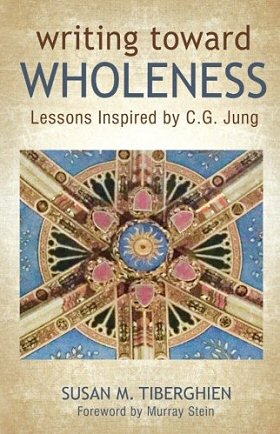

Jean-Pierre Robert interviews Susan Tiberghien, author of Writing Toward Wholeness, about the benefits of keeping your own Red Book and writing to your soul. Tiberghien reflects on her journey as a writer, the transformative power of journaling, and Jung’s influence on her work.

French version of this interview

Jean-Pierre Robert: You write that this book is the fruit of over thirty years of Jungian reading and reflections.

Susan Tiberghien: When I turned 50, I returned to my desire to write: to be a writer. I had married a Frenchman, and together we raised our six children in different countries in Europe. In order to pursue my dream, I attended a two-week writing workshop in the United States, which helped me retrieve my mother tongue.

I began publishing short stories and leading workshops for writers while immersing myself in the works of great writers and spiritual masters. I was particularly intrigued by C.G. Jung, a scientist who also spoke of the soul. His autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, inspired me to take courses at the C.G. Jung Institute in Küsnacht near Zurich and to enter into analysis.

These years of reflection and inner exploration led me to discover myself—as a wife, mother, writer, teacher, and researcher. Today, I continue on this path toward wholeness through writing, reading, and prayer. It is this thirty-year journey that I share in Writing Toward Wholeness.

Murray Stein, who wrote the preface to your book, states: « Any person can benefit from keeping a journal of experiences, dreams, associations, and feelings. »

In his insightful Foreword, he goes on to say:

« This project is for self-knowledge… We write in a journal to become and to know who we are. »

Therefore, the real work in journal writing is a work on oneself.

Marion Woodman, in her book Bone, Dying Into Life, describes journal writing as a way to talk with herself:

« I hear my truth resonating in my own daily experience. »

Today, I continue to converse with myself in my journals. Once we open the door to the unconscious through writing, as through dreaming, the depths only continue to deepen.

There are many accounts of Jung advising his analysands to write everything down. You mention his counsel to Christiana Morgan, noted in her analysis journal from 1926.

Jung’s counsel to Christiana Morgan is addressed to each of us today:

« I should advise you to put it all down as beautifully as you can, in some beautifully bound book […] it will be your church—your cathedral—the silent places of your spirit where you will find renewal […] for in that book is your soul. »

Jung advises us to write down our dreams, our reflections, and our desires. Our journals become our chapels, where, in the silence, we converse with our soul.

My journal is not a large beautifully-bound book. It fits into my purse so that it is always close at hand. When I reread the pages, I find the traces of my soul. I do not write each day. Rather I write when I wish to understand something, when I wish to deepen a thought, when my soul calls to me.

Then the journal becomes a door to the unconscious. I enter the imaginal world and listen to who is calling me. I look to Jung as an example—his years of confronting the unconscious, his search for his soul. I have read and studied The Red Book in depth. The way he engaged with each image, what he would later call active imagination, has become my own way of bridging the conscious and the unconscious.

In the dictionary, wholeness is defined as the condition of a person who has reached the highest degree of development, who is at the peak of their strength, intensity, and completeness. Is there a connection between wholeness and the concept of totality in Jung’s work?

I clearly see the connection between wholeness and the notion of totality. Jung himself addresses it when he recounts his final dream to Ruth Bailey:

« He saw a big round block of stone in a high bare place and on it was inscribed: This shall be a sign unto you of wholeness and oneness. »

However, I perceive a spiritual meaning in the word wholeness that I do not find in the word totality.

In my book, I define wholeness as the oneness of all creation. In the word oneness, there is a sense of harmony that I do not associate with the word totality.

It is this feeling of harmony that Jung experienced in his last years. In Memories, Dreams, Reflections he writes:

« There is so much that fills me: plants, animals, clouds, day and night, and the eternal in man. The more uncertain I have felt about myself, the more there has grown up in me a feeling of kinship with all things. »

A feeling of kinship with all things, with plants, animals, clouds, with the eternal in humankind.

It is this sense of kinship, harmony, and communion that I am searching for in Writing Toward Wholeness.

Your book is filled with numerous examples. What are the main rules of keeping a journal ?

I would say there are no rules. There are a thousand ways to keep a journal. It is the practice that counts: to sit down and write freely. The choice of journal, pen, place to sit, time of day, and the amount of time dedicated—everything is to be discovered.

I do suggest a time limit in order to avoid writing pages and pages. Since I see journaling as a way to deepen our life, sense of self, and relationship with our soul, I propose a slow writing and meditative writing. Often half a page suffices to touch our soul.

I will, however, offer one rule: note the day, time, and place. This way, you will be able to more easily locate where you were and rediscover « the silent places of your spirit where you will find renewal. »

You evoke the role of writing in the lives of Thomas Merton, Etty Hillesum, and many other authors.

I would like to highlight the fundamental importance of writing for Thomas Merton, Etty Hillesum, and C.G. Jung.

Thomas Merton was a writer before he was a monk. He defined himself in and through his writing: the young boy who lost his parents, the undisciplined student, the wandering vagabond, the poet, the monk, the mystic. It was through writing that he was able to discover his own self: seeker of God. From the moment he entered the Cistercian monastery, he kept a journal, and it is within the pages of his many volumes of journals that he reveals himself.

Etty Hillesum, by contrast, kept a journal for only three years, from the age of 26 in 1941 until her death at Auschwitz in 1943. She began journaling to uncover the strength to continue living through the nightmare that surrounded her as a Jew in Amsterdam during the height of the Nazi genocide.

In searching for that strength within herself, she found God. Day after day, she chronicled the discovery of her soul. Three months before her death, she was able to write in her journal, An Interrupted Life:

« The beat of my heart has grown deeper, more active, and yet more peaceful, and it is as if I were all the time storing up inner riches. »

I now turn to C.G. Jung, who emphasizes the importance of writing down our dreams, active imaginations, and conversations with our soul. In Mysterium Coniunctionis, Jung describes active imagination and concludes with this advice:

« Fix the whole procedure in writing at the time of occurrence for you… [for] that will counteract tendency to self-deception. »

It is all too easy to not believe what our soul is whispering to us.

This is exactly what Jung did when he returned to his black books in 1913, after setting them aside for several years. He began writing down his confrontation with the unconscious and later transcribed it into The Red Book with artistic calligraphy.

For sixteen years, Jung continued to write commentaries about each vision, maintaining his dialogue with his soul. As Murray Stein writes in the Foreword:

« He undertook a risky venture and survived. For us, the risks are not so great because we have his story of the journey as a support. »

To keep a journal is to keep a record of a journey, a voyage of the soul toward God.

To conclude, can you share three key elements for successfully keeping a journal that will accompany us on our journey toward wholeness?

The first element: our journals are our own red books. To ensure they accompany us on our journey toward wholeness, we must fully engage in the writing. We must truly want to write. Each of us seeks to better understand ourselves, and keeping a journal is one way to do so. Jung counsels us to engage in this practice.

The second element is to sit down and write. It’s easy to put it off until the next day, but to make this practice meaningful, like prayer, try to devote at least half an hour each day, or even just fifteen minutes, to journaling. If you prefer, you might dedicate an hour every two days. Find your own rhythm and stick with it.

The third element is to be sincere in what you write. There is no room for artifice in journaling. We cannot disguise ourselves, pretend, or put on a facade. When we write in a journal, we are alone with ourselves in front of the empty page.

When our journals are sincere, they become our chapels: the sacred space where our soul finds a home.

Thank you, Susan Tiberghien, for taking the time to share your work with us. We highly recommend Writing Toward Wholeness to anyone looking to embark on this adventure.

Original interview conducted by Jean-Pierre Robert,

translation by Susan Tiberghien.

Susan Tiberghien

Susan Tiberghien, an American-born writer living in Geneva, Switzerland, has written five memoirs and two nonfiction books. She holds a BA in Literature and Philosophy (Phi Beta Kappa) and did graduate work at the Université de Grenoble in France and at the C.G. Jung Institute in Küsnacht, Switzerland.

She teaches at C.G. Jung Societies, the International Women’s Writing Guild, and at writers’ centers and conferences in both the U.S. and Europe.

Her website is: www.susantiberghien.com

Learn more

- Darkness and Light in Seasons of Love—an interview with Susan Tiberghien & Catherine Chevron-Tiberghien, conducted by Peggy Vermeesch

- Writing Toward Wholeness—an interview with Susan Tiberghien, conducted by Jean-Pierre Robert